A research about the Ainu of the island Hokkaido (Japan). The Ainu used to live on the islands of Kurily, Sakhalin, Tohuku and Hokkaido. Through out the history their islands were passed to and fro among the Russian Empire, Japan and (later) Soviet Union.

A Hole, a Door and a Tree

A hole is a mysterious phenomenon. It is morphologically absence of material, and yet it is presence of something else. It can be considered an entrance or an exit. I see it as an opening, a beginning of a passage to the unknown. It is a border between here and there.

Doors and windows are the most visible ‘holes’ of a building. Windows could be seen as the eyes for letting the visual input in, or as the ears for letting the sound in or as the nose, for conveying the smells; while doors could be perceived as the mouth for letting the tactile senses come into play. All the ‘holes’ of a living being – allowing for intake of nutrients, air, visual and audio stimuli, procreation, and disposing of the waste. Holes in our clothing allow the cloth to be shaped, fitted and arranged around our bodies – the openings for the neck, the arms, and the legs.

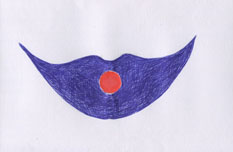

The indigenous people of northern Japan, the Ainu, created intricate patterns on their clothing. The most famous is the “attus” – a coat-like garment made from elm bark fibre, decorated with maze-like black-and-white application. The patterns surround the openings of the garment – the neck, the sleeves and the hem. They are meant to protect from evil. The symbol of “{}” parentheses forms the base. The religious and spiritual life of the Ainu is based on animism, a belief that everything has a soul or a spirit – living and not-living entities. The Ainu lived from hunting, fishing and gathering – a lot of spirits had to be attracted and pleased or repelled and be protected from. The pattern is not only present on the clothing – the women of Ainu had a tradition of tattooing a “{“ shape around their lips and an intricate plaited pattern on the arms and hands. This was, apart from protection from evil, a sign of becoming a real Ainu woman.

Richard Tuttle, in his text “Indonesian textiles”, mentions Ainu textiles as not being rooted in their culture: “They establish roots for themselves in their own culture, not in the way even other conservative textile traditions, like Peruvian or Ainu, might extend their intricate forms beyond the topmost branches of their cultural tree – nor do these hold the warm feeling found in Indonesian textiles.” And this could be true. The pattern was meant to protect from evil, to deceive the bad spirits, to send them away from the openings and not let them even come close to the body, let alone enter it. It is interesting, though, that the very thing meant to create a maze and protect, becomes the very symbol of the Ainu culture. It is a decoration, a mask, a costume. The Ainu are dissolving in the majority – part of the Ainu conceal or find their roots unimportant, and part of them working in Ainu museums as “Ainu”. Only the pattern is left. There is probably no way to find the Ainu back; they are lost in the maze of history.